Our Problem-Framing Template (Free Download)

Problem framing can help project stakeholders get on board with precisely which problem you aim to solve, why, and for whom. In this post, we break down the problem framing process Mightybytes uses to help our clients identify the right problems and start down the road to solving them.

What Problem Are We Solving?

It’s a deceptively simple question. However, depending on who you ask or where you are in a project, this simple question can produce complicated answers.

- Choose the wrong problem and you could end up wasting time and resources or, worse, building something nobody wants.

- If your problem is too big or broad, it may be tough to solve with available resources.

- If your problem is too specific, you risk not reaching enough people to make your efforts sustainable long-term.

Every product, process, program, or service—digital or otherwise—is geared to solve some sort of problem people have. Businesses, nonprofits, and civic institutions alike often create solutions based on assumptions, and that’s a dangerous game. Challenges arise when there’s no clear consensus between stakeholders about what the problem is and how to solve it.

Fall in Love With Your Problems

Innovator Bias is a sneaky troll — rearing its ugly head, not just during ideation, but throughout the innovation lifecycle, often when you least expect it. At each step, some of the most fundamental truths come from a deep understanding of problems before solutions.

— Ash Maurya, Love the Problem, Not Your Solution

The best solutions come from teams that deeply explore the problems their customers or users have. This doesn’t happen overnight. Even with time-saving digital tools, successfully solving challenging problems takes time. Unfortunately, many teams quickly fall in love with their solutions rather than the problems they hope to solve, a phenomenon known as “innovator bias” that is common to startups and inexperienced teams.

These solutions often miss the mark because the team either isn’t solving a big enough problem or has lost sight of what their customers actually want. Relentless pursuit of problem details—versus solutions—gives projects a greater chance for success.

For Mightybytes and most agencies, the reality is that our clients typically come to us with some sort of prescribed solution:

- “I need a new website”

- “My company wants <insert technology here>”

- “We’re looking to streamline this process”

- “We have to improve our SEO”

Sound familiar? In some cases, we discover that their actual problems can’t be solved by the solution prescribed. Learning this deep into a project could cost you valuable time, money, and resources, not to mention strain a client-agency relationship.

Problem framing workshops can improve your chances for success and foster a good, collaborative project culture right from the start. They’re a critical part of the design sprint methodology and can be very useful in product roadmapping sessions as well.

Defining Stakeholders: Who’s in the Room?

Make sure you have the right people in the room for a problem framing workshop. Understanding your stakeholders is key for project success.

If you’re working with an external organization—like an agency or other strategic partner—make sure they are included. One of the biggest mistakes we see clients make is to start the process of discovery on their own, then lump findings into an RFP. This sets the project up for potential failure from the get-go. Creative collaboration doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

Attendees should represent a diverse set of perspectives, some of which have specific expertise in the problem being solved. Unique perspectives and varying viewpoints are encouraged, as is an innate sense of curiosity, optimism, and respect.

We have found that a group of 5-10 people works well. Less than that and you don’t have enough diversity of thought/opinion. More than that and things can get unwieldy to facilitate, especially if you are time-constrained.

Steps in Our Problem-Framing Process

Here are the steps Mightybytes employs to help clients identify and accurately frame their problems. We can typically get through a workshop in about a half-day, though pre- and post-workshop activities take much longer. You may need additional prompts if your attendees are hesitant or uncomfortable speaking in front of a group. You may also need additional time if there are vastly differing opinions about problem details.

1. Pre-Workshop Research, Preparation, Planning

Prior to any workshop, we do cursory research into the potential problem a client wants to solve. We ask probing questions and run searches on who has this problem, how they address it, and whether or not existing solutions exists.

This is not meant to replace more detailed user research that comes later on but instead helps us quickly validate whether some assumptions regarding the problem are correct (or not). It also helps us frame the discussion and customize the workshop deck specifically for a client’s unique needs.

We share this cursory research with attendees ahead of time or at the beginning of the workshop with the goal of giving them context and helping them stay focused on outcomes over output.

2. Writing Problem Statements

After introductions, attendees write problem statements based on what they know at that moment, then share them with the group. Typically, most folks have already given some thought to both the problem and potential solutions.

A good problem statement identifies:

- A gap or clear pain point that exists today

- When and where the problem happens

- The impact that problem has: could be money, lost time, lost lives, endangered public health, etc.

- The problem’s importance: to better understand its urgency

Some problem statements also identify a desired future state or solution. You can include this in your own statements, but don’t dwell on solutions in a problem framing workshop. There is plenty of room for that as the project evolves. Focusing too much on solutions in a problem framing workshop can lead you down a rabbit hole of lost time. Fall in love with your problems, remember?

Here’s an example problem statement from Wikihow:

Overfill has been a serious problem facing our city waste facilities for the last decade. By some estimations, our city dumps are, on average, 30% above capacity—an unsanitary, unsafe, and unwise position for our city to be in. Several methods have been proposed in order to combat this. Perhaps the most popular of these is the simplest: building two new landfills on the county outskirts. Others have proposed stronger recycling campaigns and larger per-bag waste disposal costs as a way to lessen the potential damage of our trash situation. Bluffington is close to drowning in trash. Action is needed if our city is to remain the clean, safe place to live it has always been.

A simplified version of this statement might look something like this:

Overfill has been a serious problem facing our city waste facilities for the last decade. Our city is close to drowning in trash. Action is needed if our city is to remain the clean, safe place to live it has always been.

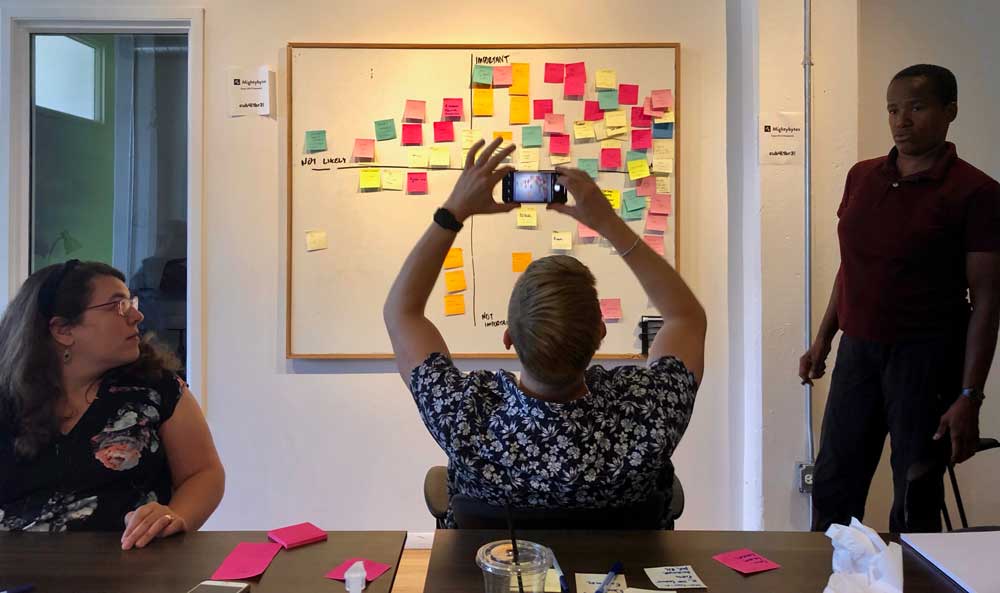

The level of detail in your statements are will vary from person to person. Each participant should write their statement out on a single sticky note that is large enough to hold the necessary copy. Sharing and discussing these statements in a safe group setting will help the team better understand similarities and differences about the problem everyone thinks we’re solving.

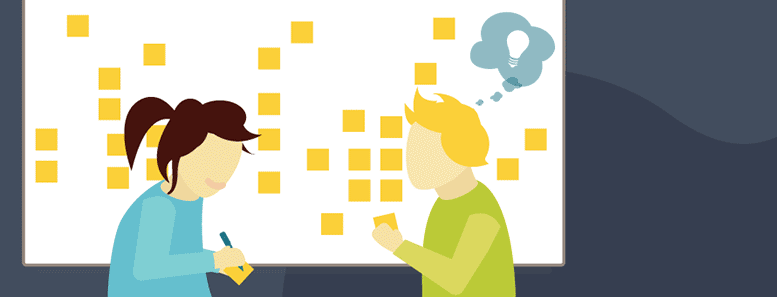

3. Statement Mapping

When discussing problem statements, you may discover that while similar themes exist, individual statements vary widely. Statement mapping focuses on impact and importance.

To map your statements:

- Create a standard x/y grid on a whiteboard.

- Label the grid lines: high/low impact, and high/low cost or value.

- Ask participants to place their problem statement on the grid based on the problem’s impact and the resources necessary to solve it.

This exercise should foster lively conversations about how best to prioritize problem-solving efforts. More importantly, it should clearly identify similarities and differences between individual statements. By the end of the discussion, your team should be able to identify which statement(s) your team interprets as the most important to address, given their complexity and the impact they could have.

Statement Voting

If a clear winner doesn’t arise from your discussion of problem statements, take a vote. Using stickers or simply an ‘X’ with a pen, each attendee votes on which statement they feel most accurately represents the problem that needs solving. Re-read the winning statement to the group.

4. Stakeholder Mapping

A stakeholder mapping exercise helps your team better understand who a given problem impacts. This is a great opportunity to keep all impacted parties in mind, even the ancillary or less obvious ones. We always make sure to include the environment as a stakeholder, for example, because it is inevitable that decisions throughout a project’s life cycle could have environmental consequences.

For the exercise:

- Thinking about the problem statement you voted on, ask people in the room to identify as many stakeholders as possible, one per sticky note, on the table in front of them. Be specific. Include individual names or organizations, if necessary.

- Create an x/y grid, this time labeling the axes as ‘impact’ (high/low) and ‘involvement’ (high/low).

- Ask team members to place their sticky notes on the grid based on:

- How impacted a stakeholder is by this problem.

- Their likelihood of getting involved in creating the solution.

- Discuss opportunities the map represents.

BONUS: If time allows, an ecosystem mapping exercise can also be helpful. During this systems thinking exercise, team members identify an organization’s entire ecosystem through the lens of a given project.

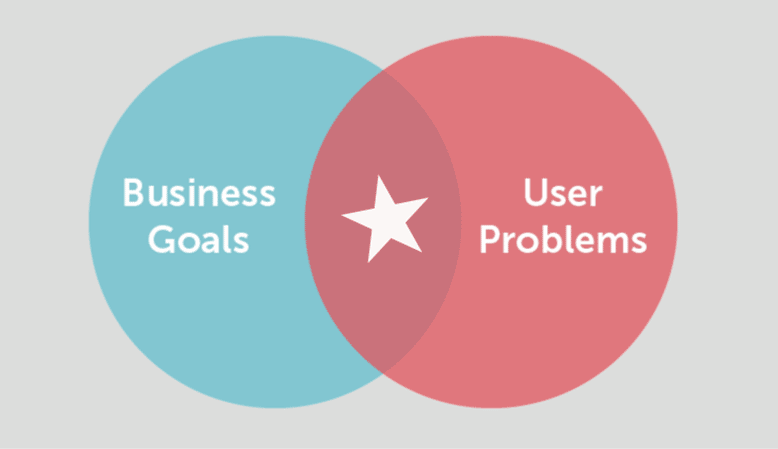

5. Business Goals & User Problems

The next set of exercises define your organization’s business goals as well as the problems users or customers have. To run this exercise, draw two large intersecting circles on a whiteboard. Label one ‘business goals’, label the other ‘user problems’.

Business Goals

Have team members write out the organization’s individual business goals as they relate to the problem being framed. Place each sticky note in the appropriate circle on your whiteboard. This gives everyone in the room context about what your company or nonprofit needs to achieve in order to find success.

Once you have captured a fair amount of goals, ask the group these questions to facilitate a longer discussion:

- Are these your organization’s most important goals?

- How do they relate to the organization’s larger purpose?

- How are they specific to your programs, products, services, etc.?

User Problems

Next, choosing a primary user from your stakeholder map, ask the team to identify problems he or she has, one per post-it. Ask these questions:

- Why is the user’s problem worth solving?

- What if we did nothing?

- Has anyone else solved this problem? If so, how?

- What could go wrong along the way?

Be sure to stay focused on problems. It can be easy to fall into the trap of generating ideas for solutions during these exercises. Remind the team that there will be plenty of time to generate solutions in a future workshop. For now, we’re focused on problems.

Also, it is important to note that a problem framing workshop’s purpose isn’t to dig into defining users and their needs. It is merely meant to provide context and foster discussions about where business goals and user problems overlap. Here is where potential solutions lie. If conversations start getting too ‘in the weeds’ you may need to keep everyone focused in the interest of time.

6. Defining Alignment

Looking at your whiteboard, ask the team to draw connections between the organization’s goals and problems users have. Identify similarities by placing aligned sticky notes into the center of your circles. Capture the aligned problems/goals in a document that can be later shared and discussed, as this is likely fertile ground for future opportunities.

If at all possible, you want to identify a number of different areas where user problems clearly align with organizational goals. If that doesn’t happen, it is possible that the problem you hope to solve isn’t a good fit for the organization.

7. Problem Reframing

Finally, once you have run all these exercises, it’s time to reframe your problem statements. This is important because everyone thinks and communicates differently. Each person should reframe the problem based on what they learned in the workshop. This should give your team new perspectives to consider.

To do this:

- Review all existing workshop materials, including the original problem statements.

- Each person rewrites a new problem statement based on what they learned through these exercises.

- Statements are read to the group with opportunities to ask clarifying questions.

- Revise statements as needed.

Be sure to allow enough time in this exercise so that everyone in the room can appropriately review and interpret the workshop’s materials. If time allows, run a group exercise to create a final problem statement that everyone can get on board with. If not, a round of voting might be in order to save time.

What’s Next: Answering Who?

After a problem framing workshop, we often run a separate workshop to better understand users’ specific needs, or, if we’re running a Design Sprint, we will assign proto-persona homework between problem-framing and the sprint itself. Either way, it is critical to any project’s success for project teams to deeply understand their users, so make sure you devote enough time for these exercises and an appropriate amount of user research.

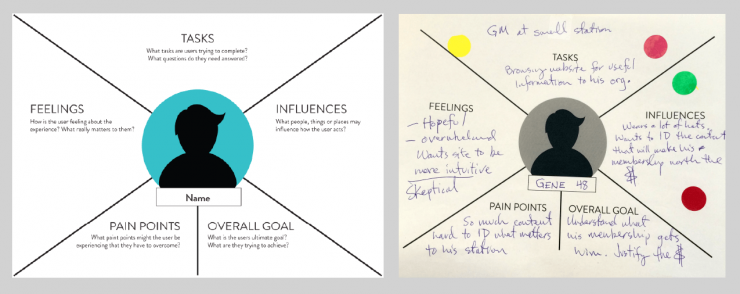

Proto-Personas & Empathy Maps

Based upon assumptions of what your team knows about potential users right now, proto-personas and empathy maps offer a great way to jumpstart the process of user research and facilitate meaningful conversations about how best to meet their needs.

Remember to remind everyone that proto-personas are based on assumptions, not detailed research as with a more standard persona approach. For more information on the role personas play in digital projects, please see our post How to Create More Inclusive User Personas.

User Research

In addition to personas, we’ll typically outline a strategy for user research based on what we learn in the problem-framing workshop. This can take many forms, from quantitative online surveys to user interviews and other techniques. For more information on how we approach user research, please see our user research and testing services page or our blog post Five User Research Methods for Better Digital Products.

Solving Problems Left and Right

Problem framing workshops can be a great way to create clarity and build group consensus about a specific problem your organization hopes to solve in the service of new products, processes, programs, and so on. Each time we run one of these workshops, it generates a slew of new insights and excitement.

NOTE: When run during an in-person workshop, the process described in this post can use a lot of sticky notes. Obviously, those aren’t happening as often (if at all) in the age of COVID-19. If you’re interested in cutting down workshop waste or need to run this process remotely, digital collaboration options exist.

Please read our post How to Facilitate More Sustainable Design Workshops to learn more. For general information on how we apply sustainability principles to digital products and services, check out our post on sustainable web design. To learn more about problem-framing in a broader project context, read our post Design Sprints for Social Impact Projects.

Download our Free Problem Framing Workshop Template

This deck can help you jumpstart the process of problem framing in your own organization.